For over a year, a county attorney in southern Minnesota was the target of a criminal investigation as detectives tried to understand whether she actually lived in the district where she was elected.

Now, nearly three years after investigators found she “does not reside” in Waseca County, Rachel Cornelius is running for re-election in the same county.

The Attorney General’s Office ultimately declined to charge Cornelius with a crime.

But the evidence, obtained by 5 INVESTIGATES through a public data request, raises serious questions that have derailed political careers in the past.

The criminal investigation into Cornelius’ residency involved months of physical and video surveillance by Owatonna police. Detectives determined Cornelius stayed at her home in Waseca just 30% of the time while spending the majority of her days at her family’s farm in neighboring Le Sueur County.

Minnesota law requires candidates to sign an affidavit of candidacy, swearing under oath that they live where they serve.

“It doesn’t mean you can kind of play games,” said political and election lawyer Charlie Nauen. “It’s a very real consequence.”

Throughout the criminal investigation, Cornelius maintained her innocence.

“The voters of Waseca County granted me the privilege of being their County Attorney,” Cornelius said in a written statement to 5 INVESTIGATES. “I reside in a community I love and will continue to zealously serve the citizens of Waseca County.”

In a recorded interview with police, Cornelius said she was surprised by the money spent on the criminal investigation.

“It just seems like a political ploy,” Cornelius said at the time.

Nauen, who has spent the last 15 years practicing political and elections law, said residency cases are fairly rare, but when it comes up, “everybody looks at it very closely.”

Political Careers Ended Over Residency

The Minnesota Supreme Court has routinely held that residency is required for local elected officials, including those involved in the judicial system.

In 2015, the court removed Judge Alan Pendleton from office after he lived in his wife’s Minnetonka home while overseeing cases in an Anoka County-based court system.

Four years earlier, the court censured and suspended former Hennepin County District Judge Patricia Karasov after determining she was living at her Chisago City lake house while also renting out her Edina townhome.

“As long as the law requires it, for elected officials, particularly those that are either judging or enforcing the law, they should be pretty scrupulous about obeying the law,” Nauen said.

Other examples involved state lawmakers accused of not living in their districts.

In 2016, the Minnesota Supreme Court ruled that three-time state Rep. Bob Barrett (R-Lindstrom) was ineligible for his legislative seat because he didn’t meet residency requirements ahead of the general election.

The most high-profile example of an elected official’s residency being scrutinized came last summer when Rep. John Thompson (I-St. Paul) handed a police officer a Wisconsin driver’s license during a routine traffic stop. Thompson, like every other elected official, signed an affidavit affirming he was a Minnesota resident – but never disclosed his address in that paperwork.

Thompson avoided any additional questions about his residency after he promised to obtain a Minnesota driver’s license, but other scandals led to him losing support from the DFL party.

Right now, the Benton County Board of Commissioners is taking the rare step of suing Benton County Auditor-Treasurer Nadean Inman, alleging she “is not qualified to hold the office” after an outside criminal investigation determined Inman was spending her time at another house in Sherburne County.

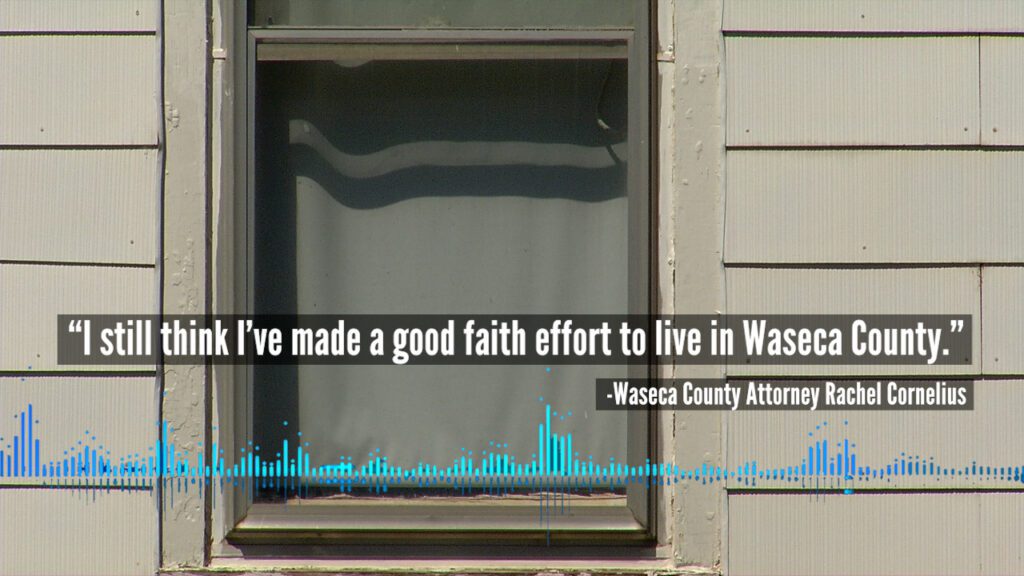

A ‘Good Faith Effort’

While elected officials can face consequences for not living where they serve, legal experts say it’s rare that they face criminal investigations. The Minnesota Attorney General’s Office ultimately decided the police couldn’t prove the allegations against Cornelius beyond a reasonable doubt.

Investigators in Waseca County found Cornelius’ family still lives in Le Sueur County, where her kids went to school. In an interview with detectives, Cornelius said it was “just kind of a fluke” that surveillance showed they were spending 70 percent of their time outside Waseca County.

“We were at the other house more, but we were still at the Waseca house though, too,” Cornelius said. “It’s not like we were pretending to live there.”

Through their investigation, police discovered Cornelius had her Waseca house’s lights on timers, making it appear she was home when she wasn’t. Neighbors on the block echoed similar sentiments, law enforcement documents reveal, but Cornelius said it was for her own safety.

“My husband and kids aren’t there all the time with me,” she said. “It’s not to like, put on a facade.”

The detective overseeing the case said he was “hoping” he could give Cornelius the benefit of the doubt that she was “making a good faith effort to be living – like actually living in Waseca.”

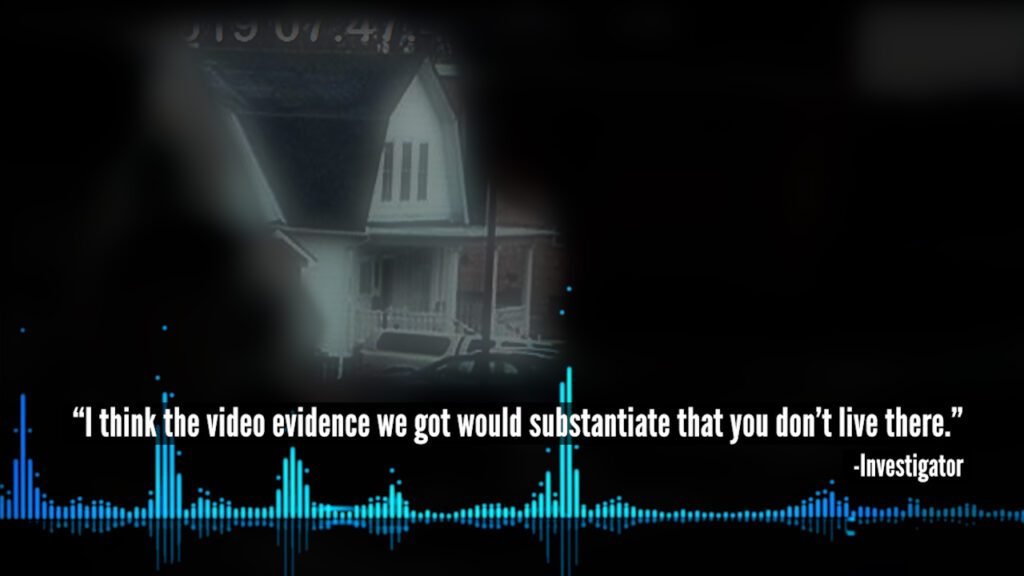

But as the investigation carried along and more evidence surfaced, police were convinced otherwise.

“I think the video evidence we got would substantiate that you don’t live there,” the Owatonna detective told Cornelius.

State law doesn’t require candidates for county attorney, sheriff, or judge to put their addresses on paperwork to run for those offices. On May 19, Cornelius signed a document swearing she lives in Waseca County.

It’s the same document she signed in 2018, six months before she purchased her house in Waseca.

“Now that I know that my life is being scrutinized,” Cornelius told police, “I am paying attention.”